More GUiT News

One night, many years ago, as I sat in the front part of our house, the surung as it was called, I heard strange noises and cryptic conversation. I wrote about it in GUiT, under the title “Dee Dee Dit - Dah Dah”, and the man with who was having this strange talk with Father amid the blaring cacophony was Pakcik Lockman, who appeared in GUiT on page 113.

Father, a Morse Code man in the Telegraph Office in Kuala Trengganu, was conversing with Pakcik (Uncle) Lockman in dots and dashes in the front room. These were heady days of technological innovation, when the blanket and smoke, and distant drums, and the cleft stick and carrier pigeons had all given way to copper wires and electricity, and telegraphy was tapped out in Morse to distant time-zones and places afar. I wrote:

”That night a friend of Father’s named Lockman was preparing to sit for his radio ham examination, and he needed Father to brush up his dots and dashes. Dee-dee-dit, dah-dah, dee-dit."And then, to my great surprise, the past linked back to the present, and it came in an email. And this is how it began:

“...about a month ago I was in Kuala Lumpur. Before returning to Kuantan, my place for the last 48 years I had a brief visit to [my] brother R. Zainal. We had a short discussion about you and how you came to know about me and that I was preparing for my radio HAM examination. I told him that there were only two persons that knew about this. Ripeng, a police wireless operator and Wan Ali (at this time we still did not know that you are the son of 'Ayoh Wang' the man who always smiled when he spoke). My brother couldn’t remember your father. He remembered jovial Wan Daud, Wan Hussain, Wan Jaafar my neighbour, 'Wei Ayoh Ngoh Meroh' his classmate and a few others.”

It was signed simply, 'Pok Mang'.

Pok Mang was of course Pak Cik Lockman,

or Raden Lockman bin Raden Saleh to give his full name. In a further email he sent me a black and white photograph of himself looking very much like a matinee star, from his days in Kuala Trengganu, taken, as he said, by Wan Mohamed bin Dato’ Perba, a photographer “who was staying near your house [near] Pasar Tanjong.”

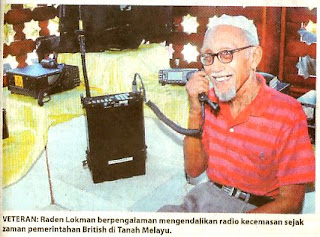

or Raden Lockman bin Raden Saleh to give his full name. In a further email he sent me a black and white photograph of himself looking very much like a matinee star, from his days in Kuala Trengganu, taken, as he said, by Wan Mohamed bin Dato’ Perba, a photographer “who was staying near your house [near] Pasar Tanjong.”Since the publication of GUiT (now into its 3rd printing) I have had many weird and wonderful experiences, been reunited with many old friends and made many new ones, and heard from quite a few people who told me how GUiT had touched them. But to be able to hear one’s own story once again, this time from one of its protagonists from times past, is a strange experience and a most satisfying one. So I would like to thank Pak Mang for having made contact. He is, I am pleased to say, still hamming it, and is most probably, at 85, “the oldest man [in Malaysia] still active in HAM radio” as he put it. And he’s sent me a cutting to show that from a recent newspaper.

And I wish him well.

And I wish him well.Labels: Morse Code, Raden Lockman, Wan Mohamed bin Dato' Perba