Then, Suddenly, I Remember...

Today, many years ago, I was reading Ralph Waldo Emerson. I was big on Ralph then, sage of self-reliance, impressive looking American (in those days when Americans were still impressive), and I was still in my early days at secondary school. I still am in my early days at school, so today I picked up an old copy of the Review section of the Guardian newspaper and read the cover story on Ralph Waldo.

It was many years ago today that a voice asked me, "Buku apa tu?". I heard it again today, as I flipped through the essay by Harold Bloom. Don't like Bloom much now, not since discovering he's a Strausser fellow-traveller, devotee of the cold-hearted, weirdo, unhinged thinker behind the present Neocon marauders. But Ralph Waldo, I can still lend him an ear.

So back to school. I was sitting at a bench in the school canteen, looking through a book I'd just borrowed from the library, Ralph Waldo Emerson. I was probably feeling a bit apprehensive then, as I felt on most school games days. When I looked up I saw a straight-haired senior in the uniform of the Boy Scouts, black horn-rimmed glasses, looking at me. "Buku apa tu?" He picked it up, flipped through it, he probably shook his head, probably nooded in approval. I can't remember.

And then I remember he was known as Ku Ali, the senior chap who stood out in school, his vivacity spreading forth as he rode on his bicycle.

And then I remember now, that was Pok Ku!

Astounded by that sudden flash, I shot him an email (which I'm sure he'll not mind if I reproduce here):

Dear Pok Ku,And Pok Ku's probably still singing now, adult numbers most probably, no more the ging gang goolie-goolie whatever. You can hear him here

Something amazing happened today. I was reading about Ralph Waldo Emerson when a strange memory flashed back. I was astounded. I began to look at it closely and the person in it took better shape, voice, straight hair, black-rimmed glasses, boy scout's uniform, bicycle, Sultan Sulaiman Secondary.

I had just joined the school then. I think one afternoon, perhaps during those dreaded school games practises. I'd just borrowed a book from the library, by Ralph Waldo Emerson, was sitting at the bench in the school canteen and reading it when a senior came and asked me, "Buku apa tu?"

He was someone I knew as Ku Ali. He was a bubbly character, a person I looked up to. You, right?

I only got the name of the teacher wrong, T.P.C****** instead of Mr N*****, who had brown-rimmed glasses (tortoise shell?). One day Mr Lau K*** B*** was briefing us all on the cross country run. "You must drink solt water," he was telling the assembly. What? Solt? Oh, Mr N***** burst out, "Salt!" All that happened in my early days at the school. And there was a boy named Lau K*** B* (also my senior).

But I remember you well, the voice, the face and all. You probably knew my cousin, N** M******* (the one who was knocked down by the Tok Peraih in one of my Growing Up pieces).

Strange how that one got dislodged from the crevasses of memory.

I probably can hear you now singing the Goong gang goolie goolie watcha, ging gang goo, ging gang goo...

Salams,

-Awang G

from Thailand with bags of salt or tiles from Senggora. These were the perahu besar of Trengganu, or the perahu bedar often seen moored in the teluk or the inlet just by the shore near our home. We had a friend named Wang Kaleh — whose real name I believe was Wan Salleh — whose father sailed these coastal waters. His name was Wang Mang — again, perhaps Wan Osman in his identity card — so he was widely known as Wang Mang Perahu Besar.

from Thailand with bags of salt or tiles from Senggora. These were the perahu besar of Trengganu, or the perahu bedar often seen moored in the teluk or the inlet just by the shore near our home. We had a friend named Wang Kaleh — whose real name I believe was Wan Salleh — whose father sailed these coastal waters. His name was Wang Mang — again, perhaps Wan Osman in his identity card — so he was widely known as Wang Mang Perahu Besar. about the pinas boats of Trengganu, Cher came back to me in a different way. The pinas, as I discovered, came to Trengganu from the French and German pinasse, which meant a medium-sized sailing boat. In the 1840s, a certain Frenchman by the name of Martin Perrot came ashore in Kuala Trengganu and married a local girl. When his name reached the Sultan of that time, Sultan Baginda Omar (1839-1876), he was summoned to the palace and ordered to design a royal schooner to match any western vessel. And so began the journey of the pinasse or pinas in Trengganu waters.

about the pinas boats of Trengganu, Cher came back to me in a different way. The pinas, as I discovered, came to Trengganu from the French and German pinasse, which meant a medium-sized sailing boat. In the 1840s, a certain Frenchman by the name of Martin Perrot came ashore in Kuala Trengganu and married a local girl. When his name reached the Sultan of that time, Sultan Baginda Omar (1839-1876), he was summoned to the palace and ordered to design a royal schooner to match any western vessel. And so began the journey of the pinasse or pinas in Trengganu waters.

Scene: Market in Trengganu

Scene: Market in Trengganu In Trengganuspeak the shaddah is sometimes used to make a verb, as in jjalang (walk), as opposed to jalang (road). But mostly it's used to shorten words, normally those beginning with the prefix ber attached to them in Standardspeak. Here again, jjalang is berjalan in standardspeak, while jalang is someone you don't speak about, well, not in polite company outside Trengganu anyway. The stress also sometimes tells you that there's a preposition amiss, the di word. If you ask someone, Mana Mok mung? ("Where's your Mum?"), and the answer is "Ddunngung," then you know that she's in Dungun (Di Dungun). "Duana mung beli nnatang ning?" ("Where did you buy this thingymathing?"). "Bbesut." But to the question: "Nak gi duane tu wei?" ("Where're you going to?"). The answer could be, "Ppasor." ("To the market.").

In Trengganuspeak the shaddah is sometimes used to make a verb, as in jjalang (walk), as opposed to jalang (road). But mostly it's used to shorten words, normally those beginning with the prefix ber attached to them in Standardspeak. Here again, jjalang is berjalan in standardspeak, while jalang is someone you don't speak about, well, not in polite company outside Trengganu anyway. The stress also sometimes tells you that there's a preposition amiss, the di word. If you ask someone, Mana Mok mung? ("Where's your Mum?"), and the answer is "Ddunngung," then you know that she's in Dungun (Di Dungun). "Duana mung beli nnatang ning?" ("Where did you buy this thingymathing?"). "Bbesut." But to the question: "Nak gi duane tu wei?" ("Where're you going to?"). The answer could be, "Ppasor." ("To the market.").

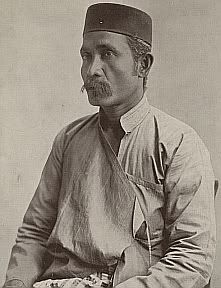

with that magnificent 'tache and the Malay songkok, that purposeful look to a distant place. And I've been asked if he is me. If you've done your MouseOver on the person you'll have found out that he isn't. So now it's time to reveal his true identity.

with that magnificent 'tache and the Malay songkok, that purposeful look to a distant place. And I've been asked if he is me. If you've done your MouseOver on the person you'll have found out that he isn't. So now it's time to reveal his true identity.