Growing Up In Trengganu #391752

In his shop, Pak sat beneath coils of ropes of nylon, twines of hemp and raffia, shrouding himself in vinegar that wafted in the air. He kept it in a tempayan in the back of his shop, down two steps on the storage floor. He had corrugated zinc for roofing in his backyard, and bits of wood for minor repairs, and lengths of bamboo sticks, and fish-hooks, and nails for both concrete and wood, and some sharp enough to give the pontianak a funny tingling in the shoulder. But we didn't have too many pontianaks in Trengganu then, so the demand for nails came mostly from local builders and DIY-ers, not bomohs on the look-out for ghostly high-jinks in the air. Pak sold the nails by weight, and judged them by hun, which was a measure of the depth of nails for the houses of Trengganu.

Pak wore gold teeth and a soft skull-cap called the ppiyoh lembek, and underneath it he wore a perpetual smile. He was a belt and braces man who wore the sarong pelikat, underneath which he wore his working trousers. When he was sat behind his hardware display, pickled in the wafting aroma of vinegar in the deep claypot, he rolled up his sarong maybe a foot or two to signal that he was at work; then at 5 o'clock he'd lower it again to his ankles, then he'd roll the long haji's wrap around his cap before closing the shop and cycle in the direction of the muezzin's call.

I could judge the time of day by Pak's routine in his hardware shop, or by the blaring voice of Radio Malaya that came out of a giant foghorn-shaped hardware jutting out from Bhiku's first floor window. This was public information radio that made Bhiku's customers stir their cups with a tra-la-lee, and sit up on the alert with the constant tooting of the time-signals. I can't remember any of the news items that followed, try as I may, but I remember still the lyrics of R.Azmi coming from there that opened up a young mind to the delights of a faraway place and the charms of a sassy lady. I knew she waddled like a duck, in the afternoon light, with waist so trim and fastened tight. "Itu dia, Nona Singapura...itu dia, Nona Singapura." Ah, the delightful Singapore lady!

That was the sound as Pak cycled past the punters by Bhiku's shop on his way to the house of prayer, when market traders were just letting down their hair in there over steaming cups of milky tea and trading insults or homilies while waiting for the man in the back to shout over the din, "Roti kaya!" The "roti kaya" was, and still is, a slice taken from the long white loaf called roti bata (pillow bread), then toasted over a charcoal fire, then smeared with Planta margarine and topped with the shop's own specialty of kaya, a local spread made from egg-yolk, with pandan leaf for flavouring, and then thickened and sweetened with sugar and flour.

Sometimes Pak would stop at a coffee shop if he chose to close early, but he wouldn't go to Bhiku's but to another one next-door to his that had a more conducive clientele. Bhiku's had a more diverse company of fish traders and wayfarers, and strangers freshly arrived on shore. There was a man in a stiff round cap who lived in the top floor of Bhiku's shop right behind the fog-horn shaped radio speaker. He'd been there for years and years and walked with an A3-sized flat display box that was always wrapped in a sleeve of thick material when he was out on his early morning calls. I never knew what he had, but I guessed that it contained stones like akik and zamrud and delima; agate, and emerald and ruby. He was known to us as orang Kabul, the man from a land far away.

As the light faded, and the ladies of the village were out at the community well, vans and lorries arrived in the wide space between Bhiku's and the general market, carrying vegetables and fruits, sugar canes tied up in tall bundles, bananas from the groves of smallholders and onions in baskets called jok, from China perhaps, or maybe India. Occasional traders from the ulu sometimes arrived on trishaws hailed at the jetty, with forest fruits like ngekke, salak, pulasan, perah, and sometimes those mini, yellow, soft-skinned fruit called simply buah ssakkor. Bhiku's busy waiters would then take in another pile of cups to wash, or unwrap another loaf of roti for these hungry deliverers of goods for the market of the morrow. Just in time they came for the procession of ladies with young helpers with smaller sized baskets in hand, or tall kerosene lamps — the pelita ayam — already lit to guide the way of deep basins of house-cooked food carried by lady traders for their evening food stalls that traded long after Pak's done his last solat of the day and hung his clothes that bore just a little whiff still of the back-room vinegar.

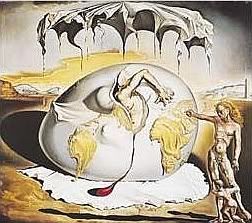

"Bathing in Trengganu" by the very talented Malaysian artist Anuar Dan; reproduced by kind permission.

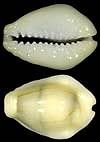

The shell's smooth surface is then moved over the surface of a piece of cloth — part of a man's apparel, probably the sampin — which we also call the selepang — that's wrapped around the waist in a Malay costume, or a woman's full suit, made of fine cotton cloth. What the pressure of the cowrie shell did was it polished the cloth until it shone alluringly in daylight, and made a lady even more enchanting, bedecked in the glitter of reflected light. And then she or he would be truly jangok. Winstedt says that jangak, is a harlot, or pilferer or a sneak-thief in Perak, and is the same word that means someone who's smartly dressed in Kelantan (or Trengganu), but here I part company with him. Jangok or janguk has no connection with jangak and is just a way of looking very smart.

The shell's smooth surface is then moved over the surface of a piece of cloth — part of a man's apparel, probably the sampin — which we also call the selepang — that's wrapped around the waist in a Malay costume, or a woman's full suit, made of fine cotton cloth. What the pressure of the cowrie shell did was it polished the cloth until it shone alluringly in daylight, and made a lady even more enchanting, bedecked in the glitter of reflected light. And then she or he would be truly jangok. Winstedt says that jangak, is a harlot, or pilferer or a sneak-thief in Perak, and is the same word that means someone who's smartly dressed in Kelantan (or Trengganu), but here I part company with him. Jangok or janguk has no connection with jangak and is just a way of looking very smart.

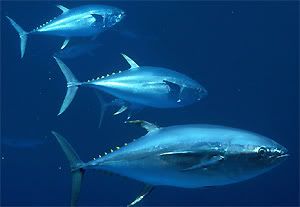

Looking at the sinigang recipe which I plucked from the web, I'm more convinced now that it is indeed singgang, except that in Trengganu we never put a chicken into our earthen pot.

Looking at the sinigang recipe which I plucked from the web, I'm more convinced now that it is indeed singgang, except that in Trengganu we never put a chicken into our earthen pot.

Then, covering it carefully with the lid, she'd leave it aside to mature, until the bones of the fish are soft a couple of days later when she'd rise early and put in more ingredients into the pot to transform the singgang into a coconuty accompaniment to the nasi dagang, rice that's such a ritual to make that I'll now take my leave and let the ladies get on with the work.

Then, covering it carefully with the lid, she'd leave it aside to mature, until the bones of the fish are soft a couple of days later when she'd rise early and put in more ingredients into the pot to transform the singgang into a coconuty accompaniment to the nasi dagang, rice that's such a ritual to make that I'll now take my leave and let the ladies get on with the work.

Yesterday while walking in Covent Garden in Central London, after finishing the above blog, I began to think of Pak Mat because there, near the famous piazza, is an address that constantly reminds me of my alleged identity. In 1821, when Thomas De Quincey was flat broke and desperate, he obtained lodgings in a house there and started to write the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, but did not finish it there as he soon had to flee his creditors. His Confessions appeared in the London Magazine where it received much acclaim. By its publication he also brought to the attention of the wider public that the Malays were an amok prone people.

Yesterday while walking in Covent Garden in Central London, after finishing the above blog, I began to think of Pak Mat because there, near the famous piazza, is an address that constantly reminds me of my alleged identity. In 1821, when Thomas De Quincey was flat broke and desperate, he obtained lodgings in a house there and started to write the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, but did not finish it there as he soon had to flee his creditors. His Confessions appeared in the London Magazine where it received much acclaim. By its publication he also brought to the attention of the wider public that the Malays were an amok prone people.

the man who ccuri ayang. He's the resident chicken thief. The chicken is central to

the man who ccuri ayang. He's the resident chicken thief. The chicken is central to

Kelosong, said the Kelantanese, was derived from the French croissant, because — she claimed — the kelosong was crescent-shaped. Give a little twist of the Kelantan tongue, and the croissant became the kelosong.

Kelosong, said the Kelantanese, was derived from the French croissant, because — she claimed — the kelosong was crescent-shaped. Give a little twist of the Kelantan tongue, and the croissant became the kelosong.