Those who hemmed and nudged and gave knowing looks after reading my account of being chased by a shoal of

kerepok lèkor off Batu Burok (See Goneng’s bio-data in the sidebar) should read this man’s account of his light repast in Kuala Trengganu:

”We were persuaded to stop at a coffee shop and eat some doughy sea creature which looked like a monstrous sausage.”

That was, no doubt,

kerepok lèkor, the fast-swimming, sausage-like, doughy textured ancient sea creature that lurks in the warm waters of our Trengganu coast, ever the scourge of shoreline swimmers, but delicious once incapacitated and decapitated and thrown into a cauldron of boiling water.

The man was Stewart Wavell, a Cantabrigian on an expedition with his university mates in the East Coast of peninsular Malaysia in search of old wives and hoary tales, when he stumbled on Pulau Redang, about which he waxed lyrical:

“I have seen beaches in many parts of the world as far apart as Florida in the United States and Ramree Island off the Arakan coast of Burma, but none have the innocent loveliness of Redang. Before it is too late, and certainly before this book has been too widely read, I pray that the Trengganu Government will preserve Redang forever as the last island of our dreams. Let it be sacrosanct. Let no one land upon its shores. Let it grow in legend like the Greek islands where the sirens sang. When all the beauties of Trengganu have been unveiled before the searching eyes of tourists up from Singapore, let this one beauty remain. For Redang is to Trengganu as the semangat is to the paddy, or the soul to the religious man.”

This was 1963, of course, and strong winds have blown many things off course in many directions since then, Monsoon Cup and all.

But the enchanted Redang that so captured the imagination of Wavell was where he and his team went in search of two old characters, one from behind the misty legends of old Trengganu, named Awang Kayak Semerah Muda; and another, Che Tahir bin Seman. The former came through the latter, an old storyteller who lived in the nearby island of Pulau Pinang, “in the lee of the Redang”, sheltered from the strong waves lashing ashore during the bleak monsoonal weather.

Awang Kayak was a picaresque character who fell in love with Mèk Hitam but caught the eye of Dayang Sri Jawa, a princess from Java who came asailing to Trengganu on a boat named

Beliong Panjang. Awang of course married them both and still found time to cavort with seven Siamese princesses, one of whom bore him a child.

The story ended inconclusively as many old tales did, but before leaving, Wavell asked Che Tahir if he knew who the seven princesses of Siam were. “Ah,” replied the sage, “you will be wise to leave them alone in the past. Bring them back to life and they will use their charms and snares upon you and you will never again return to your loved ones in England.”

Five years earlier (in another book), Wavell was pottering about on the shore of Lake Bera (in Pahang) with his recording instrument when something moved him to turn back for the camera. It was then, he claimed, that he heard the bellow of the Naga (dragon) of Bera. He described the wail of this monster thus: “It was a snort: more like a bellow — shrill and strident like a ship's horn, an elephant trumpet, and sea lion's bark all at once.” Regaining his composure, he switched on his tape recorder (a Uher?) and held up the microphone in the air, but alas, unlike the seven princesses of Siam who (as Wavell was to find out years later) used their hair to bind Awang Merah Muda hand and foot and then forced him to make love to them all in one afternoon, the Lake Bera inhabitant proved to be very shy. Wavell waited vainly with his tape recorder for a reprise of the wail.

Small recompense: he discovered, as we've seen above, another creature in the water, the

kerepok lèkor, when, gripped by forlorn hope, Wavell arrived in Trengganu and saw light at the end of the tunnel. “Trengganu is a woman whose beauty is veiled,” he wrote. “She is poor with shabby clothes, but let a breeze lightly lift a corner of that veil, and the stranger finds himself victim of a curious restlessness — an urge to explore enchantments customarily concealed.”

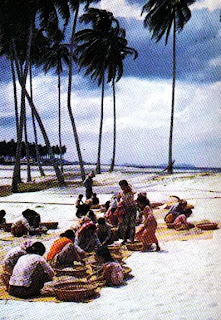

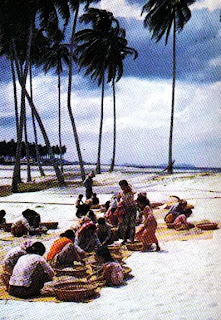

Photo: Women cleaning fish (

ssiang ikang) on Trengganu shore.

_____________________________

Wavell, S,

The Naga King’s Daughter; George Alen & Unwin Ltd, 1964.

Wavell, S,

The Lost World of the East; London: Souvenir Press, 1958.

Labels: Awang Kayak Semerah Muda, Che Tahir bin Seman, Naga, Pulau Redang, Stewart Wavell, Tasek Bera

I recently found a man doing the Ota-Ota in a nice looking neighbourhood in Trengganu (thanks to my informant Pak Cik Fazli), and here he is (the Ota-Ota man, I mean, not Pak Cik Fazli who is now too busy with their new-born child), from the book by Wavell [see A Distant Cry below]. What interests me, besides the tasselled sword, decorated shield and intense look on the Ota-Otaist is the cummerbund around his waist, a kaing lepas Barat no doubt, which is, nowadays, a rarity.

I recently found a man doing the Ota-Ota in a nice looking neighbourhood in Trengganu (thanks to my informant Pak Cik Fazli), and here he is (the Ota-Ota man, I mean, not Pak Cik Fazli who is now too busy with their new-born child), from the book by Wavell [see A Distant Cry below]. What interests me, besides the tasselled sword, decorated shield and intense look on the Ota-Otaist is the cummerbund around his waist, a kaing lepas Barat no doubt, which is, nowadays, a rarity.