Before the internet blunted our pens and access to our addresses was via the letterbox, letter-writing held more for us than present day emails. There were pillar-boxes and postmen on their bikes, and human contact between deliverer and recipient that makes me ache for that beautiful film

Il Postino.

In Kuala Trengganu our postman (we had one living next door to us named Awang Cek, but he never delivered our letters) left our daily mail at the bottom of the stairs, inserted between the electrical wiring and the wood panelling. They were mostly bills, and occasionally, a postcard, but Eid al-Fitr brought a bigger bulk from all over.

Malay letter-writing is an intricate art, not least by the forms of address that we have to muster.

"Kehadapan Ayahanda yang dikasihi..." when writing to your beloved Dad,

"Bonda yang diingati serta dikasihi...", to your dear Mum, followed by a series of good-wishes with the most minimalist formulation being

"semoga berada di dalam keadaan sihat walafiat sentiasa". But we cherish the contents of penned letters though nowadays we hardly remember the contents of emails. Part of the enjoyment of letter-writing is the personal contact we have with the sender of the letter, the writer’s cursive hand, thoughts collected in a moment of joy, emotion, sadness. It is as if the person is speaking to us personally. Indeed, in films, whenever a letter appears in close up, the voice of the sender will soon fill the air, reading the letter as if in conversation with the recipient.

Other joys also come with the letter,

its tactile pleasure, the scent of perfume that some love-crazed paramour sometimes sprinkled on its page, and sometimes they come registered and hefty in weight, to be signed-for by the recipient with trembling hands. Is this the final note, a job offer, a postal order? That which plops out of an envelope is forever remembered, its memory sometimes shared, and with it, perhaps, laughter. Often at another’s expense.

Father never tired of telling about our neighbour — his schoolmate — Ayöh Wang Mamat. Wang Mamat once fell a bit under the Trengganu weather, so he penned a letter to his teacher to explain his absence. At the end of the note, he wrote, in impeccable Jawi,

"Harap Cikgu pahang." Pahang if you’re not

au fait with Trengganuspeak, is a state of understanding, and not, in this context, our neighbouring state made famous by the

joget.

In his adult life Ayöh Wang found work in

kerepok and brass, and from the number of times I stumbled on earthen jars hidden in the darkness beneath his house during games of

to I came to know that he was also a practitioner of the dark art of

budu.

Father moved on to the Post Office.

Those were days when telephones

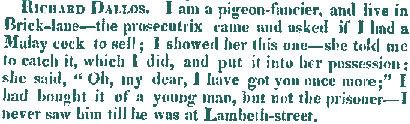

and telegrams were under the same roof of the Pejabat Pos. I knew from stories that Father told that he was once a telephone operator. These were days when calls had to go through the exchange through the operator, and the stories he told were harmless ones meant purely to amuse. One, I remember, involved a hilarious telephonic conversation between a very important man in Trengganu with his counterpart in a neighbouring state. He told us stories about his work too and about a curious room called the "Dead Letter Office". Then he donned headphones and became a Morse code operator in the Telegraphic wing of the Post Office. I don’t think he ever sold stamps over the counter though he was an avid collector with a small leather bag full of Empire stamps and First Day Covers that came through the post from a man named Dawood in South Africa.

I don’t know where "dead letters" went to, but I know that the "live" ones that reached their addressees were often treasured and remembered. I have in my possession still many letters from Father, mostly in sombre mood, written in beautiful Jawi over many pages of his writing pad. Father once told us about his father (our grandfather Tok Wan) who gave A.E.Coope a hedgehog as a present before he left Trengganu, and then, a bit later (after the man Coope, the compiler of the English-Malay dictionary) had had the animal well and truly stuffed, he wrote to Grandfather in his handwritten Jawi. The

landak (hedgehog) he said,

kohor sari kohor baik.

The charm of letters will not die even — especially — the old ones that bring back many scenarios and emotions to the reader. Recently, while looking through an old copy of the

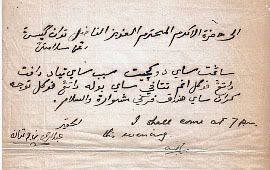

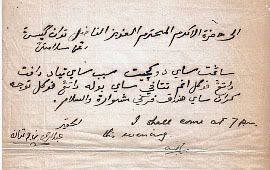

Kitab Canai Bacaan a Malay Reader compiled by the scholar Za’ba (first edition printed 1925; 3000 copies), an old Jawi note fell out from its pages, and it said:

"Sangat saya dukacita sebab saya tiada dapat datang pukul enam tetapi saya boleh datang pukul tujuh kerana saya hendak pergi mesyuarat wassalam."

The sender of the note was one Abdul Rahman bin Haji Othman, a man who must have been of some importance from the

mesyuarat that he had to keep. Also, he was an English-speaking sort of chap. As a subtitle to his Jawi note he also wrote in English: "I shall come at 7 pm this evening."

I know from the note

who the book (that we picked up from an antiquarian bookshop) once belonged to, as the note was addressed: "

Ila hadhrat al-akram al-muhtarim al-‘aziz al-fadhil Tuan Guest, dengan selamatnya." This would’ve been 1932 or later (the edition I have was reprinted in Singapore in 1932, 20,000 copies), and it was sold by the secondhand bookseller "Persama Store" for 60 cts (sen). The note was still intact when the book was finally bought by us, so I’d like to guess that it was Mr Guest who spent the 60 sen at Persama all those years ago, kept the book handy on his writing desk in Malaya (and into which he inserted the note from Encik Abdul Rahman). On Mr Guest’s passing, the book, I guess, was consigned once again, with the inserted note, to the second-hand bookshop.

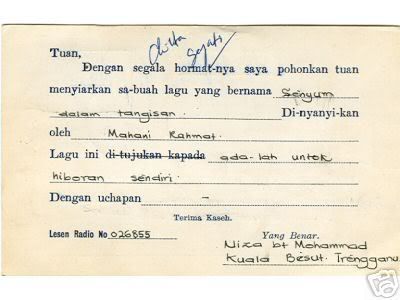

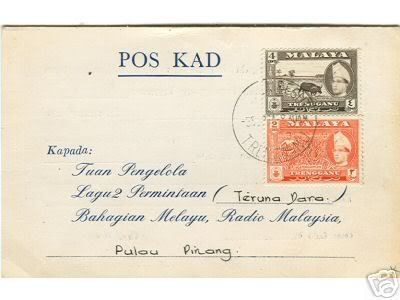

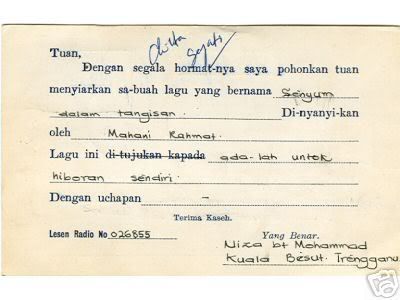

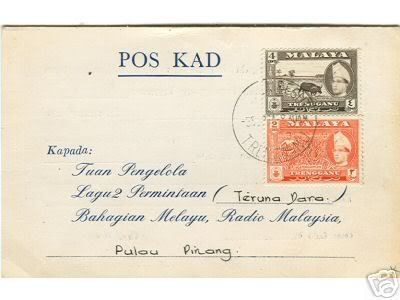

But thanks to another note from the past and to a lady from Kuala Besut, we are able to end this with a cheerful tune. I was looking through e-bay one day when this postcard [

see above] leapt through time and space (and the radiowaves), and the dial of my steam-powered radio lit up once again with some joyful old song.

Front, Song Request Postcard from Kuala Besut to the youth programme 'Teruna Dara' of Radio Malaysia, Penang.Who nowadays goes to the Post Office to drop a postcard to hear a song? "Niza Bt Mohammad of Kuala Besut, what's cooking today? I'm sorry we can't play the song

Senyum Dalam Tangisan that you requested, but here's something to keep you humming,

Cinta Sejati. Keep smiling!" [See Producer's note written over the request card.]

in Kuala Trengganu though we did not pay them much heed, perhaps because being coastal kids we had many fish to fry. But on some days the murai (magpie) would sit by our well to pour forth a long story and Mother would stop her work to say, "Bawök ssini berita baik, Cik Mura!" ("Magpie, bring us the good news!").

in Kuala Trengganu though we did not pay them much heed, perhaps because being coastal kids we had many fish to fry. But on some days the murai (magpie) would sit by our well to pour forth a long story and Mother would stop her work to say, "Bawök ssini berita baik, Cik Mura!" ("Magpie, bring us the good news!").

its tactile pleasure, the scent of perfume that some love-crazed paramour sometimes sprinkled on its page, and sometimes they come registered and hefty in weight, to be signed-for by the recipient with trembling hands. Is this the final note, a job offer, a postal order? That which plops out of an envelope is forever remembered, its memory sometimes shared, and with it, perhaps, laughter. Often at another’s expense.

its tactile pleasure, the scent of perfume that some love-crazed paramour sometimes sprinkled on its page, and sometimes they come registered and hefty in weight, to be signed-for by the recipient with trembling hands. Is this the final note, a job offer, a postal order? That which plops out of an envelope is forever remembered, its memory sometimes shared, and with it, perhaps, laughter. Often at another’s expense.  and telegrams were under the same roof of the Pejabat Pos. I knew from stories that Father told that he was once a telephone operator. These were days when calls had to go through the exchange through the operator, and the stories he told were harmless ones meant purely to amuse. One, I remember, involved a hilarious telephonic conversation between a very important man in Trengganu with his counterpart in a neighbouring state. He told us stories about his work too and about a curious room called the "Dead Letter Office". Then he donned headphones and became a Morse code operator in the Telegraphic wing of the Post Office. I don’t think he ever sold stamps over the counter though he was an avid collector with a small leather bag full of Empire stamps and First Day Covers that came through the post from a man named Dawood in South Africa.

and telegrams were under the same roof of the Pejabat Pos. I knew from stories that Father told that he was once a telephone operator. These were days when calls had to go through the exchange through the operator, and the stories he told were harmless ones meant purely to amuse. One, I remember, involved a hilarious telephonic conversation between a very important man in Trengganu with his counterpart in a neighbouring state. He told us stories about his work too and about a curious room called the "Dead Letter Office". Then he donned headphones and became a Morse code operator in the Telegraphic wing of the Post Office. I don’t think he ever sold stamps over the counter though he was an avid collector with a small leather bag full of Empire stamps and First Day Covers that came through the post from a man named Dawood in South Africa. The charm of letters will not die even — especially — the old ones that bring back many scenarios and emotions to the reader. Recently, while looking through an old copy of the Kitab Canai Bacaan a Malay Reader compiled by the scholar Za’ba (first edition printed 1925; 3000 copies), an old Jawi note fell out from its pages, and it said:

The charm of letters will not die even — especially — the old ones that bring back many scenarios and emotions to the reader. Recently, while looking through an old copy of the Kitab Canai Bacaan a Malay Reader compiled by the scholar Za’ba (first edition printed 1925; 3000 copies), an old Jawi note fell out from its pages, and it said: who the book (that we picked up from an antiquarian bookshop) once belonged to, as the note was addressed: "Ila hadhrat al-akram al-muhtarim al-‘aziz al-fadhil Tuan Guest, dengan selamatnya." This would’ve been 1932 or later (the edition I have was reprinted in Singapore in 1932, 20,000 copies), and it was sold by the secondhand bookseller "Persama Store" for 60 cts (sen). The note was still intact when the book was finally bought by us, so I’d like to guess that it was Mr Guest who spent the 60 sen at Persama all those years ago, kept the book handy on his writing desk in Malaya (and into which he inserted the note from Encik Abdul Rahman). On Mr Guest’s passing, the book, I guess, was consigned once again, with the inserted note, to the second-hand bookshop.

who the book (that we picked up from an antiquarian bookshop) once belonged to, as the note was addressed: "Ila hadhrat al-akram al-muhtarim al-‘aziz al-fadhil Tuan Guest, dengan selamatnya." This would’ve been 1932 or later (the edition I have was reprinted in Singapore in 1932, 20,000 copies), and it was sold by the secondhand bookseller "Persama Store" for 60 cts (sen). The note was still intact when the book was finally bought by us, so I’d like to guess that it was Mr Guest who spent the 60 sen at Persama all those years ago, kept the book handy on his writing desk in Malaya (and into which he inserted the note from Encik Abdul Rahman). On Mr Guest’s passing, the book, I guess, was consigned once again, with the inserted note, to the second-hand bookshop.