Growing Up In Trengganu

Never let it be said that your childhood is lacking in cakne though many will contend that it is a growing-up pain. In the Hikayat Awang Sulong Merah Muda, a tale that purportedly took place in Pati Talak Trengganu, though it came mostly from the memory of that splendid folklorist of Perak, Pawang Ana, the wasterel came home when the cockerels were crowing and dewdrops were beginning to glisten like pearls on blades of grass, before taking on again the pomegranate colour of dawn. This was youth with gay abandon when gayness was an expression of your heart, nothing to do with your sexual orientation.

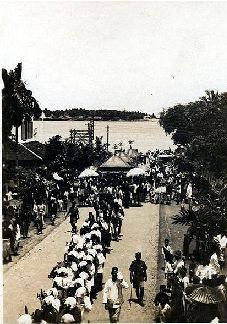

Kuala Trengganu from the air

Now, this is wayward behaviour that is born of dök cakne, and cakne is something I've been hunting like the snark and yet am still nowhere near the door of its birthplace. I hear though the mother's words, "Döh nök wak guane, dia dök cakne setabok döh le ning!" The boy's mother that is, not cakne's because cakne's Mum has left us without a trace. So without corroboration I can only say that one who is without cakne is one who does not pay any heed to what one's mother or elders are wont to say. "Döh nök wak guane, dia dök cakne setabok döh le ning!" What can I do, he doesn't listen to me any more these days!

These are the tekök boys brigade of the babe (pronounced bah-bay), two words to describe the lack of cakne. It is from little dök cakne that big waballagho lads do grow. And a waballagho person is a goner, neglectful of his duties, uncaring of behaviour and is probably also possessed of a loose tongue and looser morals. Waballagho and lere are two Trengganuspeak words that metamorphosed from one Arabic mother, lagha, i.e. to make null or void. Children may start by being a little naka (Standardspeak, nakal, naughty) though some may take it a little further and become songor. Where songor becomes bedo'oh may hang on the tolerance level of the adult beholder. But gong — an unnecessarily showy behaviour — may cling on till later life, to win, by popular denunciation, an act that is over the top, ddo'oh lalu. What's fascinating here is how one word that starts with one meaning in its source language ends up on a harsher note in another. Lere and laghö (from the Arabic 'invalid') finds its apotheosis in waballagho a word that now mocks its origin to describe someone probably beyond a glimmer of hope; while bid'ah, a word that is widely used by Muslim scholars to describe an innovative behaviour that leaves the norm, becomes aggravated in Trengganuspeak into bedo'oh or ddö'öh, something excessive and therefore unsound.

Hish, adults would sometimes say of certain types of childish behaviour, lekak pah ttua kö'ör! This is the type of speech that makes Trengganuspeak so out of grasp to outsiders and so foreboding of its youth. Lekak (Standardspeak lekat, stick, so, "sticks [it] to him/her..."), pah Trengganuspeak for 'until', ttua (from standardspeak tua, 'old'); but kö'ör? Well, kö'ör is an expression of anxiety or concern over the eventual outcome of a thing or act.

The essence of this is that every Trengganu parent wants his or her child to grow up tertib terning, another loan word from Arabic, tartib, but one that hasn't strayed too far from its original meaning of 'order' or 'sequence'. Tertib-terning is a form in Malay that I call ding-dong word-making, i.e. giving a word an alliterative or rhyming companion to strengthen its meaning and to embrace everything connected with it. So tertib-terning would mean not just doing something in an orderly manner, but embraces also everything connected to it. In Trengganuspeak we have many other ding-dong words, like ggura-selöröh (badinage), perosa-er (the fast in Ramadhan and other acts connected to it), and semayang-bang (the act of prayer and what comes with it), to name but three.

There's a catalogue of things that a child should not be when he or she is growing up. He must not be dök jjuruh, a mild admonition that is far removed from the standardspeak kurang ajar (Trengganuspeak kurang ajör), which is a serious charge. Dök jjuruh is a minor peccadillo, a mere lapse in good manners; but a kurang ajar person lacks good-breeding, spits out of turn and eats the akok before the Imam at a wedding (where he isn't even invited). This is many grades above gong and miles ahead of tebolah which, by the way, ends on a nasal note. Well, a tebolah is an awkward kid who eats his nekbat with his soup, wears his songkok with the sharp ends to his sides, and has a finger in every bee-hive. This is nanor without the Master's certificate, but nanor can be carried into adulthood. You just have to look around you to know that.