Distant Gongs

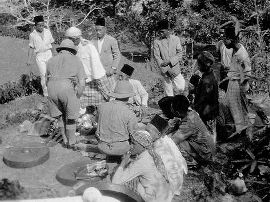

A million thanks to John Roberts who sent me the photo below where two pith-helmeted colonial enforcement officers are rummaging through the belongings of some natives to impose the "gong tax". John originally suggested to me that they could be searching for Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs), and those round objects with a bulge in the middle do look to me like massive landmines. But gongs are my best bet, as the Brits imposed a tax on land in Kuala Brang (that led to uprisings known as the perang ulu), so why not a tax on gongs too for good measure to keep them lively and hopping mad during their post-harvest ronggeng?

This photo could have been taken in Besut in the 1920s. There's reason for my saying that, as it came from the collection of a lady who was married to a colonial officer who served as District Officer (DO) in Besut around that time. His name was Mr (later Sir) Patrick McKerron, who you can see below standing in front of the DO's residence in Kampung Raja, Besut. If you've driven along Jalan Tengku Long in Kampung Raja you will have noticed this impressive house with, perhaps, the ghost of Sir Patrick lingering in the foreground; but my informant tells me that a tennis court has been drawn into that bit of lawn where he is standing.

I mentioned the perang ulu above in my spurious whimsy about the gong, but McKerron being the man on the spot and moment, did go to Kuala Brang to look into this small matter of the unrest. John gave me an amusing insight into the conduct of colonial diplomacy between McKerron and a rebel leader from Kuala Brang, but I'd like to do a bit more research in the Archives to shed more light on the man (and maybe the despatches of) McKerron. So I shall hold my blog on that for another time.

Looking again at the gong picture, I am impressed by the smart attire of the villagers and especially the well-turned out youth with the neat Haji's turban sitting in the foreground. So I believe they must have been waylaid while travelling to some special occasion, and I don't think, as John alternatively suggests, that the Tuans were each buying a gong to take home as a souvenir to their Blighty land. But then again John tells me that a Malayan gong was indeed found among the possessions of the late Mrs McKerron.