Words That Don't Mean

A departing Indonesian said something to us that made me turn to an English woman for help. She had credentials aplenty – English literature and Southeast Asian studies, and a house in Lombok where she’d lived for many years. To top it all, she worked among Indonesians in this metropolis. I thought I’d heard a familiar cry from the old Tanjong in Kuala Trengganu, in the market. “Did I hear him right?” I asked, “did he really say mari-mari before he went jalan-jalan?”

“Ah well he did,” she said, “it’s quite a common expression in Indonesia, probably of Sumatran origin.”

Mari-mari meaning “come, come!” is the familiar cry of market traders, but why did he say it as he was leaving?

The answer to that is typically Eastern, it’s a courteous statement dressed in an invitation. “I’m going now,” the Indonesian was saying, “do come with me if you want.” But of course no one was expected to follow him home.

“Do women say it too?” I asked.

“Yes, it’s used by everyone,” the English lady said.

So it’s just like the time when you open your packed lunch in front of the office crowd. You turn to everyone to say, "Makan...makan!" ("Eat...eat!"), then everyone says no, no honestly, thank you before you can comfortably begin to tuck in on your own. These are words that strike a pose but don't mean anything beyond their social import, they are the grease that makes our wheel turn.

Meetings and departures are peculiar rituals in most cultures. “How do you do?” raises the question of “what?” but it is seldom necessary to think of it like that. As it is merely ritualistic without being interrogative, most people will simply hurl the question back: “Oh, how do you do?”. But if the question then turns to “How’s your wife?” some may want to retort, “Compared to what?”

But never, never ask a Saudi man that, or your tarbouch will be knocked into a cocked hat.

“Have you eaten?” some Chinese hosts would ask, as would some Malays. The idea is to show concern over the welfare of your friend or guest. In some Indonesian islands they go one better, “Dah mandi?” is the polite concern. “Have you had a bath?” In Trengganu we are often quite cereberal and take it straight to the head. ”Guane gamök?” we ask of passing friends, “What do you think?” Of what? A better translation is perhaps “What do you make of it?” which opens it wide for the receipient: himself, the world, the day so far, the price of chicken.

To Gamök is to appraise, often by tactile means, by taking the appraised object and handling it, in your hand. The phrase dök tegamök is a useful all-purpose phrase to express distaste, an embarrassment induced by even thinking of it, or a conduct that is unbecoming though not wrong. I suppose here the mere thought of taking it — a thing, an idea, a proposal — in your real or metaphorical hand is unthinkable, outright embarrassing. ”La, ba’ape yang mung dök nniköh denge budök tu?” Well, why didn’t you marry her then?

”Hisy, aku dök tegamok eh, dia muda jjetik.” “No, I can’t do that— , she’s much too young!” In other words, I can’t handle that. So, in a sense that is now almost frogotten, gamök is a touchy-feely word.

Often someone known is met with just a one-word greeting, ”Guane!” (How?). And the stock answer to that is not how your are, or that your tummy’s upset, or your toenail’s ingrown and your ducks have stopped saying quack, but probably ”Dak guane-e, ggitulah.” (The extra 'e' in guane-e is merely there for balance). “What else can I say, it is ever thus.”

As children we used to say to leaving adults, "Nök ikut, nök ikut!" ("I wanna come, I wanna come!"), and often we were left behind dok gelepör gelenyong, nnangih wek-wek! bawling and throwing a tantrum. Is the Indonesian "Mari, mari!" connected to that, as a nod to past regrets, but secure in the knowledge that now there's no fear of the person you're addressing it to taking it up and tagging along?

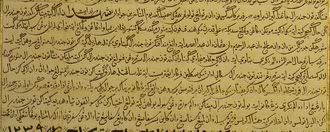

Berlin's Museum für Völkerkunde, written in ink and emblazoned in gold, and is quite a remarkable piece of work by any standard of decorative letter-writing. It came from the court of Sultan Ahmad Shah ibn Sultan Zain al-Abidin who ruled Trengganu for 18 years from 1808, and was addressed to the Dutch Governor General of Batavia, Baron van der Capellen. It is one of the most beautiful letters extant from a potentate of the Malay world.

Berlin's Museum für Völkerkunde, written in ink and emblazoned in gold, and is quite a remarkable piece of work by any standard of decorative letter-writing. It came from the court of Sultan Ahmad Shah ibn Sultan Zain al-Abidin who ruled Trengganu for 18 years from 1808, and was addressed to the Dutch Governor General of Batavia, Baron van der Capellen. It is one of the most beautiful letters extant from a potentate of the Malay world. as the letter said, a phrase I'm tempted to translate as 'junk trade', but for all its fulsome style and embroidered note, the Sultan was, as regards his cargo, modest in description: sedikit-sedikit 'ala kadarnya, he said, i.e. inasmuch as we could muster. 'Ala kadar is of course a phrase of Arabic origin that is still widely used in Trengganuspeak as a polite understatement. "Ala, takdök apa, ala kadör je!" is often said by the lady of the house to a guest as soon as tray loads of comsetibles are laid out on the table.

as the letter said, a phrase I'm tempted to translate as 'junk trade', but for all its fulsome style and embroidered note, the Sultan was, as regards his cargo, modest in description: sedikit-sedikit 'ala kadarnya, he said, i.e. inasmuch as we could muster. 'Ala kadar is of course a phrase of Arabic origin that is still widely used in Trengganuspeak as a polite understatement. "Ala, takdök apa, ala kadör je!" is often said by the lady of the house to a guest as soon as tray loads of comsetibles are laid out on the table.

She made putu ubi from the meal of cassava, she made crumbly putu from finely ground rice flour; and then for the discerning few, she made putu halba that came out piping hot in their fabric wraps, yellow as the fenugreek that she'd mixed into the rice flour. Before they cooled down she stuck on each a little square mat of banana leaf before placing them on the tray. The mat kept them from sticking to each other when packed together, six putus or seven to the ringgit, in a newspaper parcel that you clutched and hastened home before the coming of the next downpour.

She made putu ubi from the meal of cassava, she made crumbly putu from finely ground rice flour; and then for the discerning few, she made putu halba that came out piping hot in their fabric wraps, yellow as the fenugreek that she'd mixed into the rice flour. Before they cooled down she stuck on each a little square mat of banana leaf before placing them on the tray. The mat kept them from sticking to each other when packed together, six putus or seven to the ringgit, in a newspaper parcel that you clutched and hastened home before the coming of the next downpour.