Cupolas catching the morning light, glistening as they came out of the oven, six to a row, then six times again, shoulder to shoulder in the tray. Pak Mat pulled the

roti paung then dabbed ghee on them, the gleaming domed tops baked to light brown. This was Trengganu ghee, the

minyök sapi from the milk of cows of the

orang darat poured into clear glass bottles, then bunged with a rolled-up banana leaf. It curdled on rainy days into a corally yellowish-white cloud, or

tidur as Mother used to say, it'd gone to sleep. In the heat of Pök Mat's kitchen the

minyök was now wide awake, spreading easily on the bun tops, the

roti paung, lending them its rich, salty taste, and the aroma of ghee on a hot surface that was an absolute gourmet's delight.

Pök Mat went by many names, he was Che Mat Che Senani, or he was Pök Mat Nasi Minyök, but to most he was just their Pök Mat. He was a bulky man, tallish if I remember him well, as he stood there with his baker's paunch, in a white T-shirt that buttoned halfway down the chest. And his sarong — for he was always in his sarong, except on formal occasions — held loosely around his waist, but I can assure you that it stayed there all day long.

There was a crowd already at Pök Mat's gate, a couple of feet from his baking shed, and it was not yet 7 o'clock. The sunlight was soft this time of day, and the bicycling crowd of school children and the rickshaws were breezing back and forth in the morning traffic of Jalan Pantai that used to cut the coast from the hinterland of our Tanjong. The

paung kept coming out from the oven, catching the early light in their sheen, as Pök Mat stood and looked the look of satisfaction, and then he looked again as he pulled up the

sarong around his waist, and twirled the coil of cloth atop his head.

His young assistants wrapped up the

paung in newspaper sheets, two maybe for a boy to munch en route to class, or six for a family man to take home where spouse and offsprings were waiting to break the dome and set free the head of steam from within, to dunk the bread into their hot cups of milky tea or Milo carried home from the stalls in cans that once contained condensed milk.

The

roti paung was the art of Pök Mat but to me he was always the

beluda man. The

beluda was baked in a cigarette tin and stood taller than the

paung, with its shallow dome top that rose above the open round rim of the tin. You don't see or hear much of the

beluda these days, but those who remember will remember it as a spongy bread, sweet and

lemök to the taste, and was halfway between a bread and tea cake.

Lemök (standardspeak,

lemak) is a problem word as it stands between a little sweetness and richness and a little fat, and is sometimes used to describe a pleasing voice. I can feel the

lemök-ness of Pök Mat's

beluda and its soft texture in the mouth, and I hear birds singing in soft rays of light as Pök Mat's coil of rag-cloth rises like a halo above his head.

Sometimes Pök Mat abandoned his baking altogether and sold only the

nasi minyök for which he was also famous. He cooked the rice in a huge brass pot lined with a layer of fat (ghee perhaps) and when the time was right, he'd mix in green rice and red from smaller pots. So this was the nature of the mix — you'd find green grains and red in the main body of white of the

nasi minyök that came with a dab of ground chili and chunks of meat cooked in the light Malay

gulai sauce.

In coffee shops and tea stalls they served bread that stood like rows of terraced houses, baked in tins in the Chinese bakery in Ladang or in Pulau Kambing. This was the plain all-purpose bread to slice and toast, and then eaten with the

kaya spread. It was dipped in curry sauce, and in hot drinks of course, and when its soft inner dough was dug out and rolled into a ball between the thumb and index finger, it served as a useful bait for the

cicak lizard.

We bought our

roti bata piping hot from the bakery by the cemetery in Ladang, but the better loaf reputedly came from the other side of town, from the bakery of Pulau Kambing that served the best tables in Kuala Trengganu and did even better than that. In a story that many swear is true, a young would-be-

ustaz (religious reacher) was interviewed by Tuan Haji Salleh "Misbaha" bin Awang (a well-known local historian and official at the local department of Religious Affairs) when the Tuan Haji pulled a surprise.

"What do angels eat?" he asked the aspiring

ustaz.

"Why,

roti Pulau Kambing of course!" he replied.

perhaps ten or fiften paces from the minbar (pulpit), was this baroque object, with protruding parts and dangling baubles, that I often sat beside it on crowded Fridays to look at it and then marvel how on earth it did get there. We'd decided among ourselves that it was the bekas bara, for the glowing embers of wood charcoal that made the bed for the incense to burn out its cloud of smell on some special nights or days of prayer. But the nights never came for us, not even before or during the Hari Raya festival. I never saw its lid raised to take in the burning coal, in fact I never saw anyone raise its lid at all.

perhaps ten or fiften paces from the minbar (pulpit), was this baroque object, with protruding parts and dangling baubles, that I often sat beside it on crowded Fridays to look at it and then marvel how on earth it did get there. We'd decided among ourselves that it was the bekas bara, for the glowing embers of wood charcoal that made the bed for the incense to burn out its cloud of smell on some special nights or days of prayer. But the nights never came for us, not even before or during the Hari Raya festival. I never saw its lid raised to take in the burning coal, in fact I never saw anyone raise its lid at all. for having left a gap in my last blog by someone with the venerable title of Tok Pulau, who sent me an email saying: "You

for having left a gap in my last blog by someone with the venerable title of Tok Pulau, who sent me an email saying: "You  ("Isn't buah ngeker...buah tampoi?", see

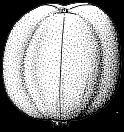

("Isn't buah ngeker...buah tampoi?", see  Looking at pictures of the tampoi I'm convinced now that it is indeed our long lost buah ngekke (Baccaurea macrophylla) which, unsurprisingly, is related to the rambai (Baccaurea motleyana). On the west coast and in East Malaysia it is known as tampoi, a name you'll immediately recognise from the location of the second most famous psychiatric hospital on the mainland, in Tampoi. (The most famous, incidentally, is also located in a place named after a fruit, in Tanjung Rambutan, Perak). In Trengganu (and perhaps also Kelantan), the fruit takes the name of ngekke which sounds to me even more like bedlam, and it's puzzled me for a long time how the fruit acquired such a peculiar name until I'm told that it is called Lang-khae in Patani, in Southern Thailand.

Looking at pictures of the tampoi I'm convinced now that it is indeed our long lost buah ngekke (Baccaurea macrophylla) which, unsurprisingly, is related to the rambai (Baccaurea motleyana). On the west coast and in East Malaysia it is known as tampoi, a name you'll immediately recognise from the location of the second most famous psychiatric hospital on the mainland, in Tampoi. (The most famous, incidentally, is also located in a place named after a fruit, in Tanjung Rambutan, Perak). In Trengganu (and perhaps also Kelantan), the fruit takes the name of ngekke which sounds to me even more like bedlam, and it's puzzled me for a long time how the fruit acquired such a peculiar name until I'm told that it is called Lang-khae in Patani, in Southern Thailand.  does not go easily from the seed, but if you suck and roll it in your mouth it gives a sweet and slightly sourish taste, unlike the tart and laxative qualities of the rambai that will soon send you running to the little house. But the most flavoursome of all from this family, they say, is the lesser tampoi (Baccaurea reticulata), or larak which I've Googled with this mouth-watering result (above). I'm not sure what larak is called in Trengganu or if it is known at all there, so if you know, please do tell me. The best I can say is that it probably isn't a name it's got but a description because, as Winstedt says, larak means "close packed (and fleshless) of pips in fruit (e.g. durians)".

does not go easily from the seed, but if you suck and roll it in your mouth it gives a sweet and slightly sourish taste, unlike the tart and laxative qualities of the rambai that will soon send you running to the little house. But the most flavoursome of all from this family, they say, is the lesser tampoi (Baccaurea reticulata), or larak which I've Googled with this mouth-watering result (above). I'm not sure what larak is called in Trengganu or if it is known at all there, so if you know, please do tell me. The best I can say is that it probably isn't a name it's got but a description because, as Winstedt says, larak means "close packed (and fleshless) of pips in fruit (e.g. durians)".

I know now where the buah perah came from, and they were not a fruit at all but seeds of a three-valved fruit that grew in the branches that spread out like arms from a tall-stemmed tree (Elateriospermum tapos) with leaves of many colours. One source says that eating too much buah perah can make the world around you spin a little, but twelve must have been a safe number as we never saw our Tanjong spin when we finished our ten sen's worth. The orang asli, the same source says, pound the seeds and bury the paste in the ground, and there it stays until they come back again to retrieve it, fermented, for use as condiment on their food.

I know now where the buah perah came from, and they were not a fruit at all but seeds of a three-valved fruit that grew in the branches that spread out like arms from a tall-stemmed tree (Elateriospermum tapos) with leaves of many colours. One source says that eating too much buah perah can make the world around you spin a little, but twelve must have been a safe number as we never saw our Tanjong spin when we finished our ten sen's worth. The orang asli, the same source says, pound the seeds and bury the paste in the ground, and there it stays until they come back again to retrieve it, fermented, for use as condiment on their food. I am also thankful to Wang Ripeng who, even as he eats his buah perah and feels slightly dizzy in the head, is still able to take some delightful shots of local trees before they disappear from this earth. He sends me this picture of the pohon bbaru which I must've mentioned at least three times a propos the diet of Kuala Trengganu goats. When we lived in Tanjong (in Kuala Trengganu), says Wang Ripeng, we kept a goat beneath our house, so we planted the pohong bbaru near our kitchen door to keep the goat in supply of its favourite snack. But in Kemamang, adds the crestfallen Wang Ripeng, the goats here care little for the pohong bbaru, preferring to chew on tufts of grass and bits of yesterday's newspaper and whatever's available in the market.

I am also thankful to Wang Ripeng who, even as he eats his buah perah and feels slightly dizzy in the head, is still able to take some delightful shots of local trees before they disappear from this earth. He sends me this picture of the pohon bbaru which I must've mentioned at least three times a propos the diet of Kuala Trengganu goats. When we lived in Tanjong (in Kuala Trengganu), says Wang Ripeng, we kept a goat beneath our house, so we planted the pohong bbaru near our kitchen door to keep the goat in supply of its favourite snack. But in Kemamang, adds the crestfallen Wang Ripeng, the goats here care little for the pohong bbaru, preferring to chew on tufts of grass and bits of yesterday's newspaper and whatever's available in the market. I've mentioned the buah terajang a few times as a fruit from our Kuala Trengganu childhood (and here I pause to shed a tear for

I've mentioned the buah terajang a few times as a fruit from our Kuala Trengganu childhood (and here I pause to shed a tear for