The light of the present has limited reach when you open the door slightly to the darkened backroom of the past. I can remember Sekolah Ladang, but only a few of my school firends' names remain intact. There must've been at least thirty pupils in that class when one day the teacher — Cik Gu Wan Chik — asked if

kucing was 'cat' or 'cup' in the English language. He was an enquirer in that instance, not in his role as pedagogue. I think I told him it was 'cup', and he left it at that, satisfied.

In the few times that I returned to Kuala Trengganu after we'd left it, I remember seeing Cik Gu Wan Chik emerging from his beach house on his Norton motorbike. I remember him smiling at me, and I hoped to God that he'd forgiven me for having misled him into leaving his cups out to catch the mice. I don't remember what he taught, or the things he wrote on the board, or any stories that he could've told to keep us quiet.

One day a man turned up in a starched uniform to stick bits of sticking plaster to our chest. We had to place half a coconut shell over it as we bathed at the well that night, to keep it dry and intact. Then the next day the plaster was lifted off our chest, and we were sorted out into 2 groups. The lucky ones, and there weren't many, were asked to move away from the crowd, while the rest were called out from the alphabetical list. My name was near the bottom, so I had time to tremble and look at the goings on that produced the

ouch! and tears. Shielded behind an empty tin of Huntley & Palmers turned on its side, a nurse was sterilising a needle in an open flame, and then, when this was quite ready (when it cooled down, I suppose and hope) the syringe was filled with some demon killing fluid and the needle jabbed on to our puny shoulders, on the left hand side. I remember being close to tears as the sharp pain lingered even as I walked away from the starched man and his nurse and her needle and the upturned Huntley & Palmers. There were boys sniffing quietly on the side, and other boys jeering at the 'softies' now emerged among us. I bear a little bump on my left side even today from that BCG jab. We were told that BCG was anti-TB, and that TB was very bad.

The Sekolah Ladang then had

atap roof and stood on low stilts over a sandy earth. In the sand lived little creatures named Cik Ru that had no discernible role in life. On those days when with Ru my heart was laden, I crawled beneath the school house to fish them out and tethered them to long strands of hair, a delicate operation that was helped by my state of extreme youth and my general lack of purpose in life. The Cik Ru then stayed in a matchbox until we grew tired of their antics, or the lack of it. At home on some warm nights we caught green beetles that tapped continuously on a matchbox with their sturdy little heads. It was nature's morse code that held the secret of the universe.

The only person I remember from Ladang, though I can't remember if he was at our school, was named Pak Ang. How a boy just slightly older than us became a 'Pak' I never knew, but he was bigger than most of us, and was a human

rempeyek for being (in our eyes) fishy, nutty and oily, and a cracker to boot. I feared him for what I thought he could have done, but I never saw him bully or beat any boy, it was just his intimidating presence that kept us all in check.

Father sent me to Sekolah Ladang early because he was a friend of Cik Gu Mat Jeng (Zain), and he thought I was better off at school than at home. Because I was a passenger rather than a fully enrolled member of the class, I enjoyed certain privileges, like turning up at school long after the others had done the lining up and tended to the plot that we were encouraged to keep. I remember walking to school one fresh bright morning after mother had combed my hair and given me all of fifteen cents; I walked to Tanjung Jamban Hijau, then cut across the

kampung to walk past the house of P. Jalil to walk daintily on a piece of plank laid across a brook that had a cluster of bamboo trees on its side. The noise that came from the trees and birds were invigorating, and it perked me up to hear the sound of people going about their daily work. It is a memory of Kuala Trengganu that is still bright in my mind, and it even carries dragonflies buzzing in the light over my head.

"..-. .- - .... . .-."In Kuala Trengganu we had a variety of people to keep our days alive: there was Cik Bagus who did odd jobs in the

pasar but declined to do hard work because, he said, it would damage his

urat kentut, (his fart channel). There was Cik Mat Lembek, the market man who wielded a stout staff to prop himself because his legs were weakened by some childhood disease — a man whom God, in His mercy, kept in full voice mode. And then Pak We came looking like a man who'd just been lifted off a horse, legs kept permanently apart. A rolled up piece of cloth, like a petrified snake, was permanently coiled around his head; he came to our house to grind spices on a stone slab, and he was, by self-acclaim, widely travelled in his youth. One day, in a distemper, he interrogated my brother about what

"Hang nak pi mana?" meant in Kedahspeak. I couldn't tell what got him into the mood or why he was eager to know from my brother who was then in no hurry to go anyplace.

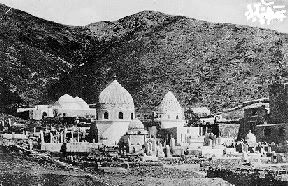

We lived in a tall spacious house built in the 1920s by workmen brought down by grandfather from Besut. Next door to us was a

surau named after a luminary called Tok Sheikh, who came, I believe, from Patani, along with many other distinguished luminaries who gave us names for our streets and places. A daily stream of people dropped by our house: friends and relatives, trades-people and wayfarers, itinerant scholars and

kitab peddlers. They sometimes stayed the night and gave us a fascinating glimpse of life on the outside: the Tok Guru from Besut, distant relatives from Patani, a clairvoyant

bomoh from Kota Baru named Pak Acu, and two Pathan friends of father who brought bales of parachute material in their car that was then, in Trengganu, a novelty cloth. They sold this brightly coloured material the next day in the market, and most ended up as shirts or blouses that put the glow into our Trengganu life.

One day, instead of the tap-tap-tapping of the green beetled matchbox in the front

surung of our house came a

dee-dee-dit, dah-dah that went on into the night. Father was a telegraph operator at the Post Office, and telegraphy in those days was conveyed by the Morse Code. That night a friend of Father's named Lockman was preparing to sit for his radio ham examination, and he needed Father to brush up his dots and dashes.

Dee-dee-dit, dah-dah, dee-dit.Even after Father retired and returned briefly to Kuala Trengganu, he never stopped being hospitable to friends in need. Before he left for Kuala Lumpur, Retnam worked as an odd job man at the Kuala Trengganu Telegraph Office (which was opposite the then C.E.B. and the Bangunan Pejabat Ugama), but when Retnam retired at the same time as Father he had no place to go, so he came and lived in the confines of our house. I remember Retnam having long chats about his Telegraphic life with a former colleague named Pak Mat, who also came to our house. Retnam was a quiet, skinny man, with lanky South Indian legs. He pottered silently in our little compound, waiting for his mood to come, and when the mood finally came, he made lime pickle that was out of this earth.

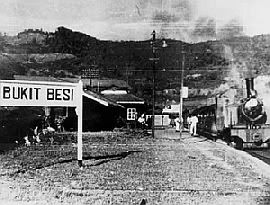

It was very hot in Bukit Besi. "Heat of the metal, you know," someone said. And then the train wended still, between banks filled with trees, stopping at Luit, Pinang, Padang Pulut, and then somewhere, into the darkness of Bukit Tebuk the bored-out hill, and there was Kemudi still, and Kumpal, Serdang, Binjai and Che' Lijah, before we reached Nibung and then it stopped at Sura Gate the station among the shops in the Dungun town by the sea.

It was very hot in Bukit Besi. "Heat of the metal, you know," someone said. And then the train wended still, between banks filled with trees, stopping at Luit, Pinang, Padang Pulut, and then somewhere, into the darkness of Bukit Tebuk the bored-out hill, and there was Kemudi still, and Kumpal, Serdang, Binjai and Che' Lijah, before we reached Nibung and then it stopped at Sura Gate the station among the shops in the Dungun town by the sea.