Hard Kor Player

To have street-cred you must have kor.

A kor is a throwing object which is used in a game. Name a game. Well, as one of you have pointed out, ggeng. There's no mystery to ggeng actually, as it features prominently in the children's calendar of many cultures; it's hopscotch. To hop, like a Scotch (presumably) or to play the ggeng, you'll need a kor to throw into the squares. So you look around for the most balanced piece of discarded porcelain, a chip off an old Ming if you're lucky, trim its corners till it's nicely rounded, then take the sharpness off its edge so that when you keep the kor in your pocket it'll not cut into your delicate areas.

A kor could have come from the sea, from the land where the kor trees grow. In its sodden, unpolished, tangled-in-seaweed state it's called buah ipir or buah gomok, and they come drifting in from the sea as ebony coloured flat seeds the size of a baby's palm. The seed has a tough, white kernel, and needs a lot to be done before it becomes a kor. A good many things come drifting to us from the sea in Trengganu: the spaghetti length rumput jjuluk that I've blogged about, the tune of the nobat, and kor. All, with the exception of the lilt of the nobat come drifting to us in the months of the musim gelora when the waves roll up in turbulent shapes and the sea spirits speak in a deafening roar. Folk don't venture out to sea these monsoon months, the sea comes to us and washes things ashore.

The buah gomok is taken home and polished with spit and Kiwi. Its kernel is sometimes left intact to give weight to the kor but often it is picked out bit by bit with a sharp stick, or cleared out in devious ways. (For a short look at the craft of kor see Long's contribution in Comments below, along with other memories on games that children play(ed) in Trengganu).

The game of wak is indeed toh or tol which basically is hide-and-seek. Wak has the added ingredient of a kor made from a milk can that's filled with pebbles, then sealed like a wedge by flattening its open rim together with a fist-sized stone, with great childish effort as to make the bibir jjueh, till the lips are pursed in concentrated intensity. This kor is the object that is thrown as far as possible when the game is played, and a person on the search team goes to retrieve it, maybe from behind a rok, a bush, then places it within a circle that's been drawn in the game area. The object is to go and catch all the players from the other side by a cot,i.e. by touching him or her, or by naming him or her on sight. For the other side, the object is to creep back quietly, then get hold of the kor and rattle it furiously in the air. Then the game is played again, hiders and catchers taking their positions status quo ante.

A game is an arduous thing and is normally played after school, near ggarib, time of the first solat (prayers)of the evening that comes soon after sunset. The object is to finish the game before bathing time at the well, then home for prayers and dinner. It's better to be a hider than searcher, but some players are born searchers, never managing to go to the one up position, much against their desire. Some just give up, returning home instead of going to retrieve the kor, leaving their tormentors hiding forever in the rak or behind the jambang, the outside toilet. Sometimes the hiders themselves collude to play a dirty trick on the searchers, and go home instead of into hiding, leaving the kor carrier on the lurch. [But see also, buah ggarek in comments below.]

A person or team that cannot play to better their position time and again is called lepek. To be a lepek is an onerous thing, and a shameful thing, for the name sticks even beyond play. To school even, at recess time, you're taunted for being a lepek, carrying the flag of defeat, of a wimp stuck in a rut, and a playground non-performer. Hence the taunting note in the verse that d'arkampo has brought back to us:

Pek pek liIn other words, once a lepek always a lepek. The opening lines to the verse is, I think, mock Arabic. We were influenced in those days by what we learned at Qur'an classes and in religious instruction, and Arabic permeated our lives, even if we spoke little of the language. The way we used to sing it was : Pek li/Watakollang... The ellision between the nonsense words watakok and lang (watakollang) gave it an Arabic flavour, as did pek li which sounds to me like the Arabic fe'li, which means 'actual', 'de facto', 'real'; from the word fi'il, activity or behaviour. We use pe'el in Trengganuspeak, to describe someone's behaviour, as in "Isy, pe'el budok ning hudoh ssunggoh!" ("This kid's behaviour is, oh my goodness!").

watakok lang

Lepek sekali

berbulang-bulang.

I don't know where kor came from, but I suspect it came from Yemeni shores, with the Sayyids on those dhows. We had many in Trengganu of such pedigree, and I can just imagine their little kids playing their little games with the locals, and producing their little kor. Except that it wouldn't have been kor that we were yet to know, but kurah, a globe, a little ball. "Apa tu?" "Ini kurah ana." "Oh, kor!"

It may not be as fanciful as you may think. Some Trengganuers probably remember our bola sekalad, our name for the tennis ball. What's sekalad? Why, from sakhlat of course, which exists both in Arabic and Persian for a woolen cloth, the texture of the tennis ball.

Then there's sakhlat ainul bana' but that's another story...

I can't thank you enough for all your wonderful comments, bringing back all those fun and games from memory, some I've forgotten, some I'm delighted to have rekindled. Those kids' verses especially are a gem. Thank you all, you wonderful people!

they have been so truncated as to become identical in form if not in meaning. As things are often remembered with feeling — of value, yearning or regret — so remembering is often accompanied with rejoicing or reproach, more often the latter. Pamuk's was with a certain sense of loss and regret at the direction the present is taking. Modernist thoughts so overcame Turkey of the Kemalists that they used to gather, amused and detached, as bystanders as wooden Ottoman houses burnt to the ground, perhaps by arsonist-modernists. I am pleased that many share my feelings about what we've lost by our deliberate acts.

they have been so truncated as to become identical in form if not in meaning. As things are often remembered with feeling — of value, yearning or regret — so remembering is often accompanied with rejoicing or reproach, more often the latter. Pamuk's was with a certain sense of loss and regret at the direction the present is taking. Modernist thoughts so overcame Turkey of the Kemalists that they used to gather, amused and detached, as bystanders as wooden Ottoman houses burnt to the ground, perhaps by arsonist-modernists. I am pleased that many share my feelings about what we've lost by our deliberate acts.

have a long history. They came in their junks from way back in the 18th century, maybe earlier, bringing goods with them and then taking local goods back to China. They settled and became cultivators, and would have also been part of the even older settlement if speculation is correct that the Fo-lo-lan, referred to by the Chinese chronicler Chou Ch'u-fei in Ling-wai Tai-ta in 1178 was indeed Kuala Brang upstream of the Trengganu river. To the Chinese, Trengganu was variously Ting Ko Nou, Ting Ko Lou and Ting Kia Lou.

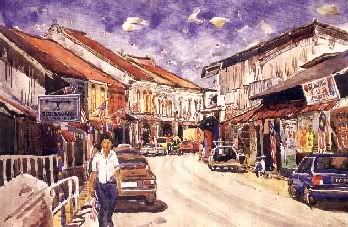

have a long history. They came in their junks from way back in the 18th century, maybe earlier, bringing goods with them and then taking local goods back to China. They settled and became cultivators, and would have also been part of the even older settlement if speculation is correct that the Fo-lo-lan, referred to by the Chinese chronicler Chou Ch'u-fei in Ling-wai Tai-ta in 1178 was indeed Kuala Brang upstream of the Trengganu river. To the Chinese, Trengganu was variously Ting Ko Nou, Ting Ko Lou and Ting Kia Lou.  reputedly owned by the Chinese translator (Low Tiey) Lim Keng Hoon in 1875. Translators served the Sultan as well as their own community, as Kapitan China. These jurubahasa as they were known, were not paid by the state, but were given powers instead to issue their own token coins, known as jokoh. One prominent Kapitan China was Wee Sin Hee, whose father Wee Kiat Kheng arrived in Trengganu from the Fuxian province in the 18th century. Sin Hee served as translator to Sultan Zainal Abidin III (1881 - 1918) and became a very successful trader who built many of the historic shophouses of Kuala Trengganu. In his Pelayaran (travels) in 1836, Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir Munshi named another Kapitan in Kuala Trengganu, one Lim Eng Huat.

reputedly owned by the Chinese translator (Low Tiey) Lim Keng Hoon in 1875. Translators served the Sultan as well as their own community, as Kapitan China. These jurubahasa as they were known, were not paid by the state, but were given powers instead to issue their own token coins, known as jokoh. One prominent Kapitan China was Wee Sin Hee, whose father Wee Kiat Kheng arrived in Trengganu from the Fuxian province in the 18th century. Sin Hee served as translator to Sultan Zainal Abidin III (1881 - 1918) and became a very successful trader who built many of the historic shophouses of Kuala Trengganu. In his Pelayaran (travels) in 1836, Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir Munshi named another Kapitan in Kuala Trengganu, one Lim Eng Huat.  There were straight trees with silvery bark that peeled off with papery consistency, that rose straight up on the side of the compound that rolled ever so slightly. I think my grandfather referred to that as the beris side, even though the beris land was commonly found by the sea, with sandy soil of the whitest purity. On a normal day, with the butterflies flitting about and my grandfather's pet birds cooing occasionally, and the soft morning light glinting off the green of the trees, the countryside gave the most wonderful sight and feel. Then a motorbike would rip past from the other end of the road, putting everything into momentary cacophony.

There were straight trees with silvery bark that peeled off with papery consistency, that rose straight up on the side of the compound that rolled ever so slightly. I think my grandfather referred to that as the beris side, even though the beris land was commonly found by the sea, with sandy soil of the whitest purity. On a normal day, with the butterflies flitting about and my grandfather's pet birds cooing occasionally, and the soft morning light glinting off the green of the trees, the countryside gave the most wonderful sight and feel. Then a motorbike would rip past from the other end of the road, putting everything into momentary cacophony. area or the jambu trees, we'd walk the quiet road past the tal trees. The tal, palmyra palm trees, were high and mighty, with leaves spreading out broader than the coconut tree, but with smaller fruits that delight the cognoscenti. (Tal, I suspect, is the Besut compression of lontar, whose leaves gave writing material to generations of Indonesian scribes, and whose nira fuelled their reverie). We'd stop by the house of Tok Nyang and hear her moan awhile. And at her age and with her skinny body that was bent almost double, she'd every right to do so. But when Tok Nyang made her jackfruit jam and gave it to us in a jar, it was as if the world and the people, and the quiet streets of Besut were all in one happy choir.

area or the jambu trees, we'd walk the quiet road past the tal trees. The tal, palmyra palm trees, were high and mighty, with leaves spreading out broader than the coconut tree, but with smaller fruits that delight the cognoscenti. (Tal, I suspect, is the Besut compression of lontar, whose leaves gave writing material to generations of Indonesian scribes, and whose nira fuelled their reverie). We'd stop by the house of Tok Nyang and hear her moan awhile. And at her age and with her skinny body that was bent almost double, she'd every right to do so. But when Tok Nyang made her jackfruit jam and gave it to us in a jar, it was as if the world and the people, and the quiet streets of Besut were all in one happy choir.